The early twentieth century journal, “Urania”, pictured above, was the brainchild of an extraordinary group of people. One of those key figures was the Carlisle born Thomas Baty. Thomas attended Carlisle Grammar School, and served his articles in the town. Afterwards, he developed a remarkable double career: he became a respected jurist, working in Japan, where he was legal advisor to the Japanese Foreign Office; but he had also a maverick side as a transgender and feminist activist! Thomas co-founded and co-edited the genderqueer journal, “Urania”, and published radical books and articles under the female pseudonym, Irene Clyde. Along with his colleagues, he campaigned in this way against the binaries of biological sex, and of social gender conventions. Such activity and awareness was unusual for the time – Thomas may nowadays be described as a transgender pioneer. He is a person of note, in Cumbria’s LGBTQ+ heritage.

“Urania” was published and circulated privately, at first six, and later three, times a year, between 1916 and 1940, by Thomas Baty and his colleagues. In fact, over the years, they bore the costs of printing and distributing the journal to, perhaps, 250 subscribers around the world. That may sound like a smallish number of subscribers, in a mission to reform the whole of society, by eliminating gender differences, and by ignoring those of biological sex. Yet, “Urania” was important to those who took it, it survived for longer than did many radical periodicals, while it was consistent and daring in its polemic critique of sexual and gender norms.

The journal’s name is an interesting choice: by 1916, Urania and Uranian were terms which had acquired significant associations. Karl Heinrich Ulrichs, a German sexologist, had written about homosexuality in a series of late nineteenth century booklets, in which he used the idea of Uranian (ultimately from Greek myth), to develop a complex taxonomy of types of male and female homosexual. (Steele, Tiernan) But the word, “Uranian”, was made better known in English through the writings of Edward Carpenter, a man who sought many reforms, especially of attitudes to homosexuality. The word, “”Uranian”, to signify homosexual, has certainly fallen out of use today, but it would have been recognised in the early twentieth century. “Urania”, therefore, had undoubted LGBTQ+ associations. But the journal had its own unique style and content.

“Urania” took as its inspiration Eva Gore-Booth’s idea that sex, as in the biological sex of a person, was an accident. Its ethos was that the “duality” of a world of two biological sexes, male and female, and of masculine and feminine gender conventions, was utterly flawed, that it cramped personal development, and that it put up harmful barriers between individuals. Sometimes “Urania” quoted Eva Gore-Booth’s phrase, sex is an accident. (Steele) Today, we would probably use the terms binary, and non-binary, instead of duality, when discussing sex and gender.

The mission statement of “Urania”, printed in every issue, declared:

“Urania denotes the company of those who are firmly determined to ignore the dual organisation of humanity in all its manifestations. They are convinced that this duality has resulted in the formation of the two warped and imperfect types….If the world is to see sweetness and independence combined in the same individual, all recognition of that duality must be given up. For it inevitably brings in its train the suggestion of the conventional distortions of character which are based on it.

There are no ‘men’ or ‘women’ in Urania.” (Tiernan, Hamer)

In fact, a Greek motto appears too, meaning, they are all angels (sexless). (Ingram, Patai) The format of the journal included an editorial, a letter section, book reviews, and a selection of reprinted articles from newspapers and periodicals around the world. This selection was a bold and pungent one. Topics covered were cross dressing, including long term transvestism; people who underwent sex changes; same sex romantic relationships; cases of intersex individuals; examples from the natural world of hermaphroditism, such as with oysters and plants, where there are both male and female reproductive organs. Life unions between women were held as preferable to conventional heterosexual marriage, and “Urania” made positive references to Sappho. (Tiernan, Oram)

To give an example, in 1936, “Urania” printed the case of a Czech athlete, Zdenka Koubkova, who underwent medical gender re-assignment to become male, and called, Zdeněk Koubek. (Tiernan)

In addition, there was a section at the end of each issue of the journal entitled “Star-Dust”, which celebrated women’s achievments in traditionally male areas, such as in science or government; in 1929, “Star-Dust” lauded the number of prizes won by women in open competition with in British goverment departments. (Tiernan, Hamer) There was also an acknowledgement of men succeeding in a traditionally female area of expertise, knitting. (Hamer)

So far as I can see, “Urania” did not debate anxiously whether something might be called homosexual, transgender, or transsexual, or another relevant LGBTQ+ word – the term, “gender” was not in fact used in the journal. (Tiernan) Rather, the whole emphasis of the journal fell on showing that personal behaviour and development were not determined by social expectations of gender, nor by one’s biological sex; even the body itself could undergo change of sex. As Niamh Carey of the Glasgow Women’s Library notes, long before Judith Butler, “Urania” was critiquing the performativity of gender. And, as “I.C.” notes in “Urania” in 1937, their motto was “Ignore Sex!”

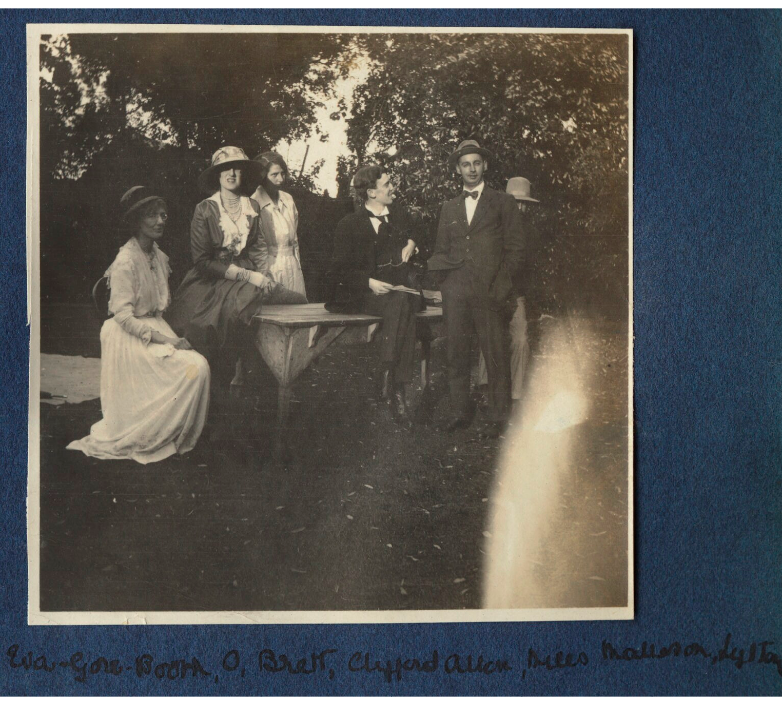

Thomas Baty contributed to “Urania” under the pseudonym, Irene Clyde, or “I.C.” Alongside Irene Clyde, Clyde’s colleagues, Eva Gore-Booth, Esther Roper, Dorothy Cornish, and Jessey Wade contributed enormously to the journal’s success. The lines of poetry which are quoted at the top of “Urania” in the photo above are by Eva Gore-Booth.

It is impossible to do justice to the diverse and radical spirit of “Urania”, and its multifold content. It was related to suffrage struggles for female emancipation, but went well beyond those in arguing that only with the dismantling of socially constructed ideas of sex, could there be equality and self-realisation. There is a spiritual element in the journal too, which downplayed the physical aspects of same sex love; while at least two of its editors were vegetarian. A possible analogy for the journal today would be that of a long-running and well put together zine – zines have an edgy quality, as does this most unorthodox periodical.

Acknowledgements:

Emily Hamer. Britannia’s Glory: A History of Twentieth Century Lesbians. London: Bloomsbury, 2016 Chapter Four, “Lesbians after the great war”, discusses Thomas Baty, Irene Clyde, and “Urania”; this includes the journal’s mission statement, its challenge to binary gender, and its diversity of contents. Women excelling in traditionally male areas is mentioned here, as is the example of men knitting.

Karen Steele, “Ireland and Sapphic Journalism Between the Wars: A Case Study of Urania (1916-1940)”, Chapter Twenty Five, in Ed. Catherine Clay. Women’s Periodicals and Print Culture in Britain, 1918-1939: The Interwar Period. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2018 Steele gives a long and helpful discussion of “Urania”, including its financial arrangements, the other editors, the term, Uranian, “Star-Dust”, and the diverse queer contents of the journal. Non-binary gender, and sex change, including “Zdenk Koubka”,are mentioned; as are Gore-Booth’s poetry and declaration that sex was an accident.

Sonja Tiernan. Eva Gore-Booth: an image of such politics. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2012 Chapter Eleven, “Radical sexual politics and post-war religion” discusses Urania, including its mission statement, “Star-Dust”, Zdeněk Koubek, and Sappho.

Tiernan mentions Alison Oram’s comments on “Urania” rejecting marriage and heterosexuality, but I have been unable to consult Alison Oram’s article, “Feminism, Androgyny and Love between Women in Urania, 1916-1940”, Media History, Vol. 7, No. 1, 2001

Eds Sonja Tiernan and Mary McAuliffe. Sapphists and Sexologists; Histories of Sexualities, Vol. 2. Newcastle upon Tyne : Cambridge Scholars, 2009 Chapter Five, “A History of Female to Male Transsexuality in the Journal Urania“, by Sonja Tiernan, discusses the history of the term, Uranian, and also in detail, the content of the journal. This includes I.C.’s injunction to ignore sex, oysters and plants, the wide range of newspaper reprintings which challenge binary gender and sexuality, and an interesting discussion of transsexuality, including the case of Zdeněk Koubek.

Chapter Nine, ” ‘No Measures of Emancipation or Equality Will Suffice’: Eva Gore-Booth’s Revolutionary Feminism in the Journal Urania“, by Sonja Tierman, in Eds Sarah O’Connor and Christopher C. Shepard. Women, Social and Cultural Change in Twentieth Century Ireland: Dissenting Voices? Newcastle : Cambridge Scholars Pub., 2008 This discusses the history of the term, Uranian, the other editors of the journal, the financial and distribution arrangements, and, in detail, the contents of the journal. “Star-Dust” is mentioned here, as is the example of women winning government prizes.

Angela Ingram and Daphne Patai. Rediscovering Forgotten Radicals: British Women Writers, 1889-1939. Chapel Hill ; London: University of North Carolina Press, 1993 These authors have done important work in identifying Irene Clyde as Thomas Baty. They discuss Urania, including its circulation, in the chapter on Thomas Baty, “The Double Life of a Victorian Sexual Radical”.

Judith Ann Smith. Genealogies of desire : “Uranianism”, mysticism and science in Britain, 1889-1940 An MA thesis, which you can download here.

https://womenslibrary.org.uk/explore-the-library-and-archives/lgbtq-collections-online-resources/the-politics-of-urania An article by Niamh Carey giving an overview of “Urania”, and listing the copies of the journal which the Glasgow Women’s Library holds.

Copies of “Urania” are also held at London School of Economics, and The Women’s Library at London Metropolitan University. Issues of “Urania” are split between these three repositories. I believe that the first twelve issues of the journal have not survived – if anybody should come across one of these, get in touch!